A communication is efficient where it is likely that the recipient interprets an expression so as to understand, the intended assertion of the communicator. The aim of this textbook's semantics section is to develop this overall principle and show how it can be applied in practice. The other principles in this section all assume this overall principle and are themselves further developments of it in a practical direction. With these principles of communication I try to give as concise and systematic account of the general theory as is necessary to allow of practical analysis of various forms of communication.

Though the principles apply with equal force to communication by both spoken and written word or other meaningful symbols the main interest is here concentrated upon the written word. This is for the practical reason that examples here must be of the written sort, but also because this is the form which predominates in the most consequential human affairs. 'Written documents are still our society's most indispensable communicative link, whether in science, the law, politics, government, the press and so on. They are also more accessible to accurate analysis than the fleeting spoken word, unless perhaps where the spoken word is permanently recorded in radio, T.V., records, cassettes and similar forms of broadcasting.

One thing that all the above-mentioned forms of communication usually have in common is that the communicator is separated from the recipient (the receiver of the communication) by the medium itself. Seldom do readers and listeners have direct access to those who publish and broadcast. This creates the sort of situation in which efficient communication is particularly uncertain and in which genuine communication can break down without either parties being aware of the fact. Semantical theory and practice aim to discover the possible sources of such malcommunication and consequent distortion and confusion of meaning through language, demonstrating both how such misuse of language arises and can be cleared up.

Understanding the intended meaning of anything one reads or hears is of course an absolute prerequisite of being able to judge its truth. If one does not know exactly what is meant by an expression, one cannot evaluate its tenability or form well-informed attitudes on its basis. The importance of being able to do this is evident from the variety of official and semi-official communication, propaganda and sales talk, laws, regulations, directives, scientific and philosophical works, political and social ideology to which we are subjected in day-to-day life or in professional connections. Above all, perhaps, the thinking person's chief source of learning about and understanding the world around us comes through the written and spoken word, so the penetration of its lack of clarity and other shortcomings become essential as a means to our understanding in general.

Thinking of our everyday conversations with people which seem quite straightforward one may well ask 'in what sense are words unclear?' Is such a theory really necessary or fruitful? Jean-Paul Sartre has pointed out that words are often either too rich or too poor. Many words in any language can have a variety of uses and nuances of meaning and this 'richness' hinders their user in making clear just how such words are to be understood.

Consider the word

'freedom' and what it may mean. Its possible 'connotations' or senses

are many, depending upon the context and situation in which it is used.

Then put to it however, it is often very difficult to say with precision

its actual meaning. The slogan 'freedom to the people' as exhibited

in a revolutionary demonstration can represent a very mixed bag of desires

from the introduction of constitutional government, of some type of

democratic electoral system, the reapportionment of land, the abolition

of unfair laws of various sorts, the improvement of economic conditions

of one sort or another, the stopping of internment of political or other

types of prisoner and so on. While all might agree with the slogan itself,

it is likely that different people or groups will understand it in very

different ways when facing the business of defining it in theory (not

to mention in practice). This example illustrates the richness a term

can have, and this applies to nearly all general terms in any language.

The poorness of words becomes a problem when one can find no word or

expression to convey the exact shade of meaning one intends. For certain

purposes it is hard to find any words in. one's own language, though

there say be exact words in other languages. Academic and literary authors

often rely on foreign terms or else coin new words, often leaving it

to the reader's intuition to guess the sense or else perhaps defining

the new term when using it. It is frequently just because of the richness

of the relevant words available in one's own language and the ambiguity

they can involve that the language appears poor, when the exact word

cannot be found to convey a singular meaning, so the richness and poverty

of language are mutually related phenomena. Sometimes, there are too

many words with too many meanings, yet too few with sufficiently few

or singular meanings.

[Note: Professor John Macmurray of London University wrote in his book

"Freedom in the Modern World": "When I undertook the

task of expressing my own philosophy in non-philosophic language, I

found, with considerable astonishment, how vague was my apprehension

of the real meaning of technical terms which I habitually used with

considerable precision. The attempt to discover their meaning proved

to be the first philosophical discipline to which I have ever submitted

and of more value for the understanding of philosophy than any scholarly

study of classical texts."]

In order to analyse this duplicity of language more systematically and

as far as possible to avoid discussing it in unclear and ambiguous words,

we need to define a number of basic terms, the meanings of which we

shall adhere to throughout this book.

Working Definitions of some Key Terms in Semantics

By ' term' we will always mean 'one or more symbols that can convey some sort of concept'. A term will thus usually contain one or more words (or other symbols) which may occur as part of a written or spoken sentence. Further, 'term' refers to the physical symbol itself, not the various meanings we nay attach to the symbol. Examples of terms are the written symbols 'shoe', 'white', 'man', 'chair', 'doing', 'if, 'as', and so on... but not the meaning or the ideas they express. Compound terms can be as follows: 'The White House', 'The Chairman of the Board of Directors', 'not both the one and the other', '210 plus 704' and so on.

By 'concept' we will always refer to 'a mental presentation that can he expressed by use of a term' 'Concept' is virtually the same as what we use the word 'idea' or 'notion' to express. It does not include the symbol or 'term' in its meaning. For example, the term 'the White House' can usually express the mental image or presentation of that building (with its 'Greek' columns in Washington in which the President of the U.S.A. holds office). The term 'chair' can express the mental concept of chairs in general, or be an image of some particular chair (such as one of Van Gogh's famous paintings of a chair), or otherwise the idea of chairmanship and so on.

It should, however, be pointed out that what are here called 'concepts' and 'statements' may perhaps not always be regarded as subjective ideas. This is because there can be an 'ideal sense' involved. Ideal sense is something independent of the individual's thinking mind and somehow belongs to the objects of thought. For example, some philosophers and mathematicians regard numbers or other 'mathematical objects' as having meaning independently of the thinking mind. The same is considered to hold true of logical relationships and (in the view of extreme realists) even of any sort of general term or expression that denotes actual classes of things or states of affairs. For the purposes of the first two sections of this book, however, it is not necessary to go further into this problem.

By 'expression'

we refer to 'symbols that can convey some assertion'. Such expression

is almost invariably compounded of two or more terms to make a full

grammatical sentence, 'expression' strictly used refers only to the

physical symbols themselves in print, graphic symbols, or vocal sounds

as the case may be. It may seen difficult to perceive an expression

in one's own language - say a written sentence - without at the same

time finding a definite meaning in it. Yet to do this is precisely what

the practical study of semantics tries to develop, strange as this may

at first seem. The aim will be to regard the expression for various

different meanings that it can express, depending upon a variety of

circumstances.

Examples of expressions: 'The President is living in the White House',

'The chairman of the board is a swindler', E=mc2 ', or simply 'GENTS

>'.

.By 'assertion'

is hereafter meant 'either the intended or the derived meaning of

some expression'. It is that which one is trying to state through

the expression of it (the intended meaning) or else that which a reader

or hearer interprets an expression to mean (the derived meaning). For

the intended cleaning and the derived meaning to be equivalent (or the

same), all depends on how clear, concise and precise the expression

and its component terms are for the person in the communication situation

involved. An 'assertion' always consists of at least one logical subject

(that about which something is asserted) and at least one logical predicate

(that which is asserted of the logical subject). The example above has

'The President' as its logical subject and 'is living in the White House'

as its logical predicate. The logical subject and predicate can be reversed

in a grammatical expression without altering their status or the meaning

as in the following two sentences: 'The President is the boss of the

White House.' (The grammatical subject is the same as the logical subject),

'The boss of the White House is the President.' (The grammatical and

logical subjects differ)

Sometimes it will be convenient to refer to both an expression and an assertion it conveys by one term. Here I shall use the

term 'statement' to mean

'a series of symbols plus their intended and/or derived meaning(s)'.

(Note that ' statement' as here defined can be used synonymously with

the philosophical term 'proposition' when written statements are concerned)

Statements are often abbreviated so that only one term or symbol remains.

Thus 'Rubbish!' stands for something like ''.That he said is rubbish!'

and 'Fire' can stand for 'Fire your rifle' or 'The place is on fire'

etc. The term 'Yes' in answer to a question is also usually an abbreviated

statement. Signs can of course make statements like "Go this way",

"No Entry" and so forth.

Statements can refer to states of affairs, but do not always do so

Consider the following

true statement:-

Eg. 'On Monday, August 6th 1945, an atomic weapon was exploded over

Hiroshima, Japan.'

This expression makes a particular and clear assertion which refers

to an established historical event. It thus refers to a state of affairs

and is true.

By 'state of

affairs' will here be meant 'an observed or observable fact that

may be asserted in a statement'. As a state of affairs pertains

only when something is or was the case, not all statements refer to

states of affairs, i.e. those having no factual reference and which

thus are unverifiable. These include those that refer only to mental

abstractions, imaginary states of affairs, relations between ideas and

non-existent phenomena. Some statements allege facts yet prove, upon

observation or investigation, to be untrue. Such untrue statements,

including direct lies, are not said to refer to any state of affairs.

The following statements do not refer to any state of affairs:-

'Imagine if black people were white and white people were black'.

'People ought only to fear doing wrong.'

'The world would have been a better place without national boundaries.'

(For a further discussion of which classes of statement are with or

without reference to states of affairs see Ch. 9 and 11).

Compound statements are common. They combine references to various states

of affairs in one sentence so that the assertion as a whole consists

in a number of separate statements.

Eg. 'It was a fine summer morning when the first atomic weapon to be used in direct warfare was exploded over Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945, killing or wounding around 150,000 persons.'

For the purposes of semantic analysis this sentence could reasonably be broken down into the following component expressions:-

Eg.- 'It was a fine summer morning on August 6th, 1945, in Hiroshima.'

'The first atomic weapon to be used in direct warfare was exploded over Hiroshima.'

'Around 150,000 persons were either killed or wounded at Hiroshima.'

Each of these statements is simple in that only one logical subject and one logical predicate is involved in each. The original sentence thus contained three distinct assertions which, when expressed separately, make three single statements.

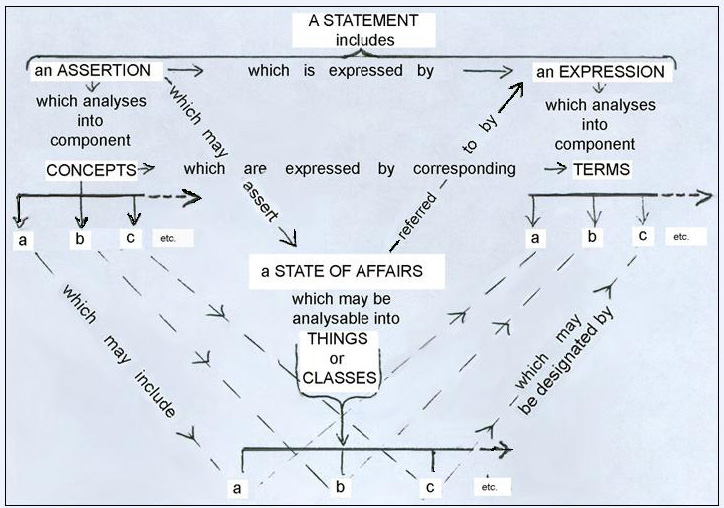

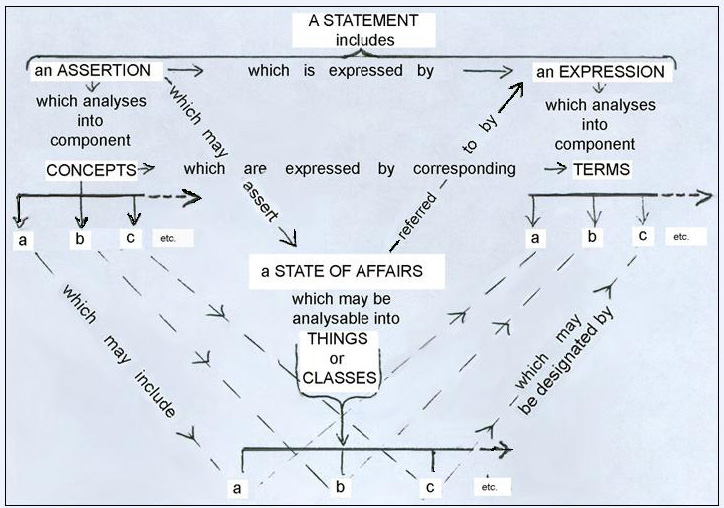

When any expression is problematical as to its meaning or its truth it may be analysed by breaking it down into component terms. Correspondingly, the assertion it can make is regarded as breaking down into component concepts

In most of our verbal activities we do not reflect as such over the concepts that make up the assertion for, when we talk or write, we seldom consciously compound our assertions out of separate concepts. For semantic purposes an analysis of the component terms and their possible corresponding concepts can be fruitful and reveal that the meaning or the tenability of a statement is problematical. Only when the meaning of a statement is clearly established can its truth or falsity be assessed. Analysis can thus show up vagueness and ambiguity that otherwise might be overlooked.

How to divide an expression into its componenet terms will depend upon the circumstances in each case, such as how many and which terms are involved, the particular syntax of the sentence, the states of affairs to which it might or might not be intended to refer, etc. Any single statement that expresses a single assertion will have both a logical subject and predicate, yet each of these may contain more than one term. The possible distinctions of meaning one can discover in each of these will help one decide the number and extent of the terms and concepts involved.

Eg. 'He behaved as if he did not understand you properly'

'He' is the logical subject (i.e. 'that about which something is asserted') and obviously consists in only one term. The remainder of the sentence is the logical predicate (i.e. 'that which is asserted - or 'predicated' - of the logical subject'). The logical predicate might be divided into component terms/concepts in the following ways:-

Eg. 'behaved as

if' - 'he did not properly understand' - 'you'.

or 'behaved' - 'as if' - 'he' - 'did not understand' - 'you' - 'properly'-

Which way to divide up the sentence will depend upon the specific purpose and circumstances involved, not upon any rule of 'correct' division terms.

Just as an assertion sometimes refers to a state of affairs, its component concepts can sometimes refer to things, objects or classes. In order to sidestep the fathomless philosophical issue as to the real nature of objects or what may and may not be classed as an 'object', I shall here simply use the terms 'thing' and 'class' (of things) in the general senses defined as follows: (3)

By 'thing' is here meant 'any distinct phenomenon that a concept may include'. Thus, things of all descriptions are included, whether they be mental or physical, natural or social. Any separate event, action, perception, state of mind or emotion can thus be regarded as a 'thing' in this wide common usage of the word.

By 'class' is here meant 'any property or resemblance common to some number of things that a concept may include'. General terms, as distinguished from particular and/or singular terms, invariably refer to a class. Proper names are singular terms, referring to only one specific individual or thing. General terms denote a class of objects, qualities objects may share, typical events or acts, characteristics that anything has in common with anything else. Thus the term 'animals' expresses a general concept of the class of those beings sharing certain characteristics. Further examples are 'snow', 'people', 'yellow', 'the fleeting', 'nation', 'gradual', 'change', 'the upheavals of society' and so on.

Clearly there can be terms with no corresponding concepts (or things/classes) and are thus those without any sense (eg. 'snark', 'slithey toves', 'bippety-boppity-boo'). Further, there can exist things and classes for which we possess no concept or term. This cannot of course be demonstrated definitively, yet the historical example of the discovery of radium supports this. Before radium was discovered, no concept of it existed. Likewise, there can be concepts without corresponding things or classes (eg. 'pure nothingness', 'living unicorns', 'furry bug-eyed monsters from Mars').

(3) Some philosophies argue that only physical entities can be regarded as 'real' objects. Others deny physical reality to objects and regard only ideal entities as 'objects'. Many intermediate standpoints are found in philosophy and the separate sciences. Whether only physical phenomena are observable, or whether observation can also be defined to include mental and emotional phenomena is an unresolved issue in philosophical debate and scientific method. If or when a concept may correctly be regarded as a thing is a complex philosophical issue best avoided at this elementary stage. If, however, one grants that concepts are real phenomena in themselves, uncertainty about the above distinction between 'concept' and 'thing' or 'class' arises. Some philosophies assert that 'concepts' are real things and some even extend this to included classes too (much as Platonism), claiming that ideal entities exist independently of the things to which they refer.

The terms defined in the foregoing and the relations between them are summarised in the form of the following explanatory schema:-

Interpretation of meaning and assessment of truth

As said earlier, only when the meaning of a statement is clearly known can its truth or falsity be assessed. However, interpreting which assertion an expression can make differs in principle from assessing an assertion's truth or falsity. Interpretation obviously always precedes assessments of truth value. Where a statement asserts a state of affairs, it is judged true if the state of affairs pertains and false if not. How this assessment is made will depend upon observational information of some sort (i.e. only in the case of statements that do assert a state of affairs).

Even though interpreting the meaning of an expression differs in principle from assessment of truth/falsity of its assertion, it is frequently necessary in practice to have some prior information of circumstances relevant to that state of affairs, before one can arrive at a reliable interpretation, One may need to know in advance a good deal about the type of state of affairs in question before the meaning of the expression can be clearly understood. For example, the statement 'The soul lives on after death' contains a term with various possible interpretations, the term 'soul'. What is actually being asserted will depend upon which states of affairs are being referred to by this term. If 'soul' is interpreted in the direction of 'the ability of having conscious experience', then the states of affairs involved will probably include the evidence of those persons who have survived clinical death (i.e. of bodily functions) yet remember intervening conscious experiences. One's assessment of the reliability of such evidence will then affect one's assessment of the truth or falsity of the expression 'The soul lives on after death'. Had one not known or assumed that the states of affairs referred to included conscious experience during clinical death, the meaning of the expression would have remained highly unclear and its truth value would have been beyond any reasonable assessment. Had one also known who made the assertion, in what context and communication situation, one would probably better be able to decide on the interpretation of 'soul' as the type of state of affairs referred to (if any) would have probably been indicated. The likely state of affairs would probably differ considerably if the communicator had been either a doctor or a Catholic priest.

Interpreting the assertion made by an expression

It is necessary to interpret an expression when it is potentially ambiguous, which is to say when it might express different assertions for different (or the same) interpreters. The overall principle of efficient communication requires that an expression is interpreted as expressing the same assertion by both the communicator and recipient(s). The distinction between 'expression' and 'assertion' implies that no assertion can be conveyed directly (we exclude the possibility of mental telepathy here). A recipient's only access to a communicator's assertion is via some form of expression. Since expressions can be unclear, ambiguous, or incomplete we require to know what factors can influence the interpretation of their intended meaning. Even when all relevant factors are known for any expression, the correct interpretation (i.e. the communicator's intended assertion) cannot be established with scientific certainty, though it may be established beyond any doubt for practical purposes. The method of so doing requires that the originator's probable assertions in using an expression be re-expressed in other words or symbols. Such re-expressions are often called interpretations, or - as in the following - also as derived expressions. A derived expression is thus an interpretation of an original expression (i.e the expression originally made by the communicator). A list of interpretations can be made where the original expression is labelled E0 and the various derived expressions are labelled E1, E2, E3 and so on for simple reference. The order of interpretations - their numbering - should not represent their relative importance or likelihood of being correct.

In the foregoing we saw that intended meaning cannot always be read from the expression itself because one expression can often make different assertions.

Consider for example

the highly general and potentially ambiguous expression

EO: "All men are equal before the law" (Let this expression

be denoted by the symbol EO as abbreviation). It could be interpreted

to mean either

El "All humans are equal before the law" (Let 31 represent one interpretation of E0) or

E2 "All males are equal before the law" (Let E2 represent the second interpretation of E0).

The different assertions made by the interpretations E1 and E2 above are derived from two different interpretations of the term 'Men' in the original expression E0. The term 'men' can mean both 'humans' and 'males'. These two substitute terms express more precisely two different concepts that can be expressed by the same term 'men'. So the term 'men' in the context of the original expression is potentially ambiguous, which is to say probably not sufficiently clear to convey the intended assertion efficiently.

We also see in this example that the same distinction applies to the relation between 'terms' and 'concepts' as applies to that between 'expressions' and 'assertions'. So we may also state that one term can often express different concepts.

In the above example two other terms are general, namely 'equal' and 'the law', both of which are potentially ambiguous. 'Are equal' could mean 'have the same rights in principle' or else, say, 'are actually treated without individual discrimination'. There can be a considerable difference between rights in principle and actual treatment. So we get four different interpretations of E0 by inserting the further interpretations of the tern 'are equal' as follows;

E3 "All

humans have the same rights in principle before the law."

E4 "All males are actually treated without individual discrimination

before the law."

E5 "All humans are actually treated without individual discrimination

before the law."

E6 "All males have the same rights in principle before the

law." This list amounts to four distinctly different assertions

that were possibly intended by the communicator of the original expression.

The meanings of the original expression E0 can be made yet more precise by interpreting the term 'the law'. 'The law' could refer to 'the law of a particular country' or 'international law'. It might even refer to some other sort of law, moral, religious or possibly even the laws of chance. The list of interpretations of EO could therefore be extended considerably by inserting different terms to bring out these conceptual differences too.

Reviewing this example it can be seen that the different assertions derivable from the expression E0 depend upon different interpretations of three of the component general terns that go to make up E0. This is frequently the case with expressions that use more than one general term.

Sometimes an expression can instead be ambiguous because its grammatical sense is unclear. For example, a personal column advert "Wanted, bath for baby, with brass bottom." Each term is sufficiently clear for the purpose, but inclarity arises as to whether 'brass bottom' is predicated of 'bath' or of 'baby' (for some people perhaps).

An expression can even be ambiguous due to the use of a term that does not refer to a general class of entities. "For example: "They paid no customs duty as they were crossing the border". Here the term 'as' could mean either 'while' or 'because', giving two different possible interpretations of what the expression asserts.

Communicating an Assertion by an Expression

Suppose there is an assertion we are thinking of expressing. If it is at all out of the ordinary run of things we are used to saying, we would probably look for a way of saying or writing it by mentally trying out different words to find those most suitable for the occasion and purpose concerned. We can often find different ways of saying the same thing. For example 'the whole earth is an ecological unit' could be expressed as 'the entire planet is one, ecologically'. There is no demonstrable difference between the two assertions made, though the expressions are different.

The above establishes another tenet upon which semantics depends: Different expressions can convey the same assertion. The same point made in other words: 'one and the same assertion can be conveyed by different expressions'. Taken together these two expressions of the tenet are also an example that demonstrates its truth.

Again, since expressions consist in terms - and since assertions can be analysed into their component concepts - Different terms can express the same concept. An example of this are the terns 'earth', 'planet', 'terra'. They can mean the same in certain circumstances, particularly where they represent the same concept for a communicator who uses them. However, the term 'planet' can also be used of the other solar satellites, which 'earth' and 'terra' cannot. Therefore these terms do not necessarily always mean the same.

It frequently occurs that we know quite exactly what we want to express, but cannot find the exact words. We may know the assertion but be unable to find the right expression. This is probably because we become aware that the expression that first comes to mind will have different possible interpretations and therefore may be taken in the wrong way.

In expressing an assertion therefore, one seeks an expression which will convey it as accurately as possible in the circumstances, taking account of the usual meanings of the words, their appropriateness in the situation they are used and for those who will listen to or read them.

EXERCISES

Analyse each of the following sentences into component expressions to make single statements:-

1) According to a representative opinion survey a clear majority of eligible voters, excluding those undecided for which standpoint to vote, were in favour of a total freeze in the development and deployment of all nuclear, chemical and biological weaponry, while a smaller majority favoured, the destruction of half of the existing number of nuclear warheads.

2) The circumstances attending the change of Soviet leadership are largely impossible to establish by foreign observers, though there are various signs to go by, such as the order in which Politburo members stand at official functions and the relative order and length of their speeches.

Analyse the following expressions into logical subject and logical predicate:

1) Those who find elementary exercises tedious and unnecessary ought not to attempt them.

2) It is usually

easy to make the distinction between male and female.

3) The swerving ball slipped past the goalkeeper into the corner of the net.