Digging among disordered old fusty books in the cellar of a Norwich second-hand bookshop (all only 50p, which is but the price of one page of photocopy nowadays), I came across 'Cricket Country' by Edmund Blunden. The author's name I had known since schooldays, but no poem or book of his had I ever read. I flipped through it and my eye was snagged again and again by charming phrases, subtle sentiments and ironic asides. This was a bargain. It soon got me to dig beneath the foundations of my mind, in those compressed and dim layers of fossil memory where I 'heard' Mr. Walters, our English master at grammar school, listing the works of this bright literary star in his personal firmament. His extolling of certain books, including 'Cricket Country', used to awaken a kind of dismay in me, for the price of any book was then far beyond my 6d a week pocket money allowance (which I was virtually forced by my aunt to save anyhow). The one consoling thought would have been that it is better to play than read about cricket. But then I was never selected by the popular cricket boys in my class for anything much other than long stop, at best, and time never allowed for me, the tail end, to get in to have a bat. They had rumbled my batting weakness and also seen that I had only so far graduated to a kind of prep. school pseudo-overarm bowling.

Now, however, a belated kind of consolation comes in the form of Blunden's ingenious interweavings of cricket memories, country associations, history, poetry, anecdotes and amusement. On the surprising ramblings through pastoral and literary bye-ways (sic) we encounter such concerns as boyhood's spontaneous cricket gatherings at improvised pitches, clergymen wicket-keepers who slaughter overpitched balls with divine vengeance, slow bowling like classical deity's physical exercises and old cricket groundmen looking like Time with his scythe with "feathery woodlands fencing us in from the world of worry". Blunden's 'dream-team' is selected from poets and even fictional characters past and contemporary, captained by Siegfried Sasoon. Blunden also relates peculiar exploits of the unofficial university team - the itinerant Paladins - for whom he played, not least on pitches so bad that old hands knew that miserable 43 was a winning score, which it was too! "...for a good part of the season the matches are played in bucolic conditions announcing the invincibility of agricultural freedom, though cow and donkey after a little parley amble off reluctantly to let the silly old stuff begin."

Blunden must have been very modest... which shows in the self-mockery of his recountings of his evidently varied (and probably not inconsiderable) exploits with ball and bat. Where it does not show as such, but exists all the more, is in the wholly unhinted fact that he was a hero of the 1st World War, an MC... later an Oxford don and a literary figure for those of sensitivity and mental refinement. I am struck by the glaring contrast between Blunden's kindliness and quiet but shrewd optimism of vision and his acute yet 'laidback' sense of enduring values with the so-called 'culture' of the present... this brash age of pulpish false invention, of Hollywood's embrace of all hateful behaviour including the penultimate in bawdiness and of the inordinate bog-ordinariness of aimless, pulpish sentiments in endless TV serials and entertainments.

Here are some samples of Blunden's gentle mind and incisive prose from the above-mentioned Cricket Country:-

As to Paladin cricket matches and pastoral moods, here is a shining sample:

"A thunderstorm is stooping over the old cricket ground in my memory. It is not a date that I can identify, and I do not know who the awaited opponents of our team are - an Estate, a Brewery, the Constabulary, some sort of Rovers, more likely just another village side. It is the forenoon, and that inky cloud is working round the hill, as black almost as the spinney of firs on the boundary, imported trees which I always suspect of being aloof in their hearts from the scene and its animations. I feel oily splashing drops and doubt if we shall have the promised encounter in the afternoon. The summer seems to have fallen into low spirits, and there is nobody about except the rooks and pigeons - we have heard all they have to say - and a crying woodpecker down under the oak at the river. The storm drifts, the cloud-edges are effaced; but the rain patters steadily on the metal roof of the mowing shed, the gutters gurgle, all the trees are grey with the shower. Past the far side of the field, a figure with a sack for hood drives his cycle apace, never turning his eyes this way for a moment; and no one from the vicarage steps out to see if there is any prospect of play.

Yet the hours pass, and after all the rain had wearied, and stopped. The smoky-looking day may remain thus, neither better nor worse, and the turf is good. A bicycle is being pushed through the meadow gate by a cricketer in flannels under his mackintosh, and one by one they all assemble. An unlocking of padlocks and shifting of benches in the pavilion, a thump of bats and stumps being hauled out of the dark corners. The creases are marked, and the offer of a bowling screen rejected..."

While on the origin of the cricket ball, Blunden digresses to the origin of the balls of all kinds, including other spherical objects:-

".. a Balloon, which, short of the grand terrestrial ball and others similar but larger, may be held to be the most dignified form of all these orbs and rondures; I have been told that it also provides the finest sport or pastime which any of them do - but the balloonist who held this opinion had really failed as a cricketer." (p. 168)

Comparing various games (unfavourably) to cricket, Blunden went on:-

"Those colossal orgies of angling for fish like 4000-pound bombs which I have only seen at the pictures appal me, and numb me; the bloodstreaked battle between the terrible and cunning sea monsters and the inflexible and ingeniously furnished humans who have hooked them to their relentless rods is not my idea of a summer's joy. Much more intriguing is the slow fellow with his float and bit of weed on the hook, hoping for one of the roach who have been stuyding the art of angling under their weir since leaves were green. I have yet to consult a Toreador on the hidden graces and intellectual pleasures of his profession, but I cannot help thinking that it is "monotonous for the bull" and dependent on emotions which need not be added to what we have to bear." p. 169-70

"... it is one of the secrets of the great games that the Losers, the majority of us, are such regular and valuable performers. We toil on happily, in every corner of the world, "the hoyps and scraps" upon whom the great ones base their triumphs; without us where would they be? We do not grudge them their glories, but we have our private world in which after all we feel comfortable enough. The Good Egg occasionally glitters all gold for us there, and we do not complain because it is not delivered by the score or the gross. Someone should pay us a juster tribute than the innumerable cartoons and lampoons that have been tossed at us as we made our way back from the scene which we had braved even if we had not adorned." p. 158

Blunden muses slyly on the possible but quite unlikely beginnings of the game of cricket as something descended from a form "of remote worship and ceremonial, of the wisdom of the ancients, of history that has gone into darkness", and then, ironically:-

"It may have been conceived by some religious layman as a variation on the old theme of good and evil in contest, white spirits and black; a popular extension of the dramatic forms in which this holy war was seasonally set before the community. The virtuous soul, resisting the deadly sins, militant against the hosts of the prince of darkness, might be the type of more that a show and spectacle; might be enacted with fortitude and vigilance by the young men who possibly tended to drift away from the high imagery on the players' platform in the market-place. Any batsman will agree that the natural bias of batsmen is toward magnanimity and beauty of soul, while that of bowlers sets sedulously towards malice and uncharitableness - even their appearances of sympathy are full of guile - and this class of beings is leagued with encircling fieldsmen of a similar predatory purpose; above all, there is one, a wicket-keeper, lurking ever behind, practically invisible, heavily armed, "shedding influence malign." " (p. 162)

"Not so very long ago (since this book is not intended to consist of antiquarian yearnings) my father and mother stopped on their walk to watch a village game on a green not far from Chichester. and were rewarded by seeing as he arrived at the fall of a wicket a figure who is more often found in books or talk than in the present scene. The blacksmith with his working clothes and leathern apron on was marching out from his shop to get his innings, and he looked as sturdy a smith as ever moistened his hands with spit; which he did with sublime vigour as he got his bat ready for huge blows at any ball in reach. I forget if his hammering was as successful here as in the glow of his fire." p. 66

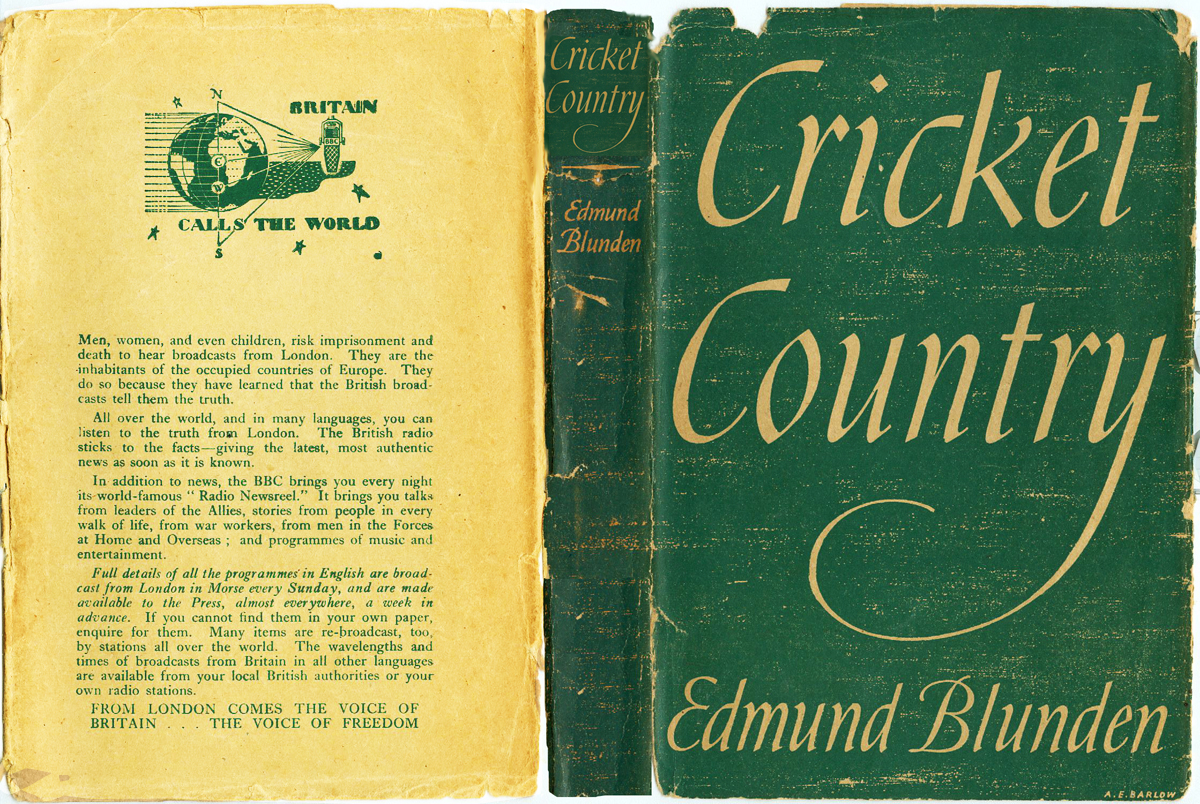

Inside the flyleaf (see scan below) of my 1945 reprint copy, I found two loose printed handouts... each entitled 'Broadsheet', from the Reprint Society of Wray Coppice, containing reviews of the books and short biographies of authors. They were from May and June 1945 respectively and the former of these contains the following biographical notes:-

AN ENGLISH STYLIST - Author of the May book "Cricket Country" : Edmund Blunden, eminent poet and essayist, interpreter of the English scene, University Don, impeccable stylist who, for the last quarter century has engaged, among others of a select company, in brilliant rearguard actions in defence of English writing traditions, numbers, among other loyalties and enthusiasms, cricket, choral singing, fishing, painting, penmanship and English country life and ways.

Edmund Charles Blunden, M.A., F.R.S.L., was born in 1896 and brought up in Kent where, as a boy, he worked at odd times in the hop gardens to earn money for books. When he entered Christ's Hospital School, which had a strong tradition in handwriting, he discovered an inherited talent for calligraphy. "One of the griefs of my life," he records, "is not to have won the School's Gold Pen." Specimens of his penmanship have, however, been included in books on the subject. He was at Queen's College, Oxford, and had published verse when the first World War intervened. He enlisted in the Royal Sussex Regiment, saw much active service in France and Belgium, was commissioned and won the M.C.

"My coming into public notice as a writer," he states, " was due to my sending an early volume to Mr. Siegfried Sasoon in 1919, when he was editing the literary page of The Daily Herald." He was awarded the Hawthornden Prize in 1922 for his poem The Shepherd. Two years later he went to Tokyo as Professor of English Literature at the Imperial University. On returning to England in 1927 he attained a high level of creative effort and wrote verse and prose in abundance. His novel Undertones of War immediately too a place among the few permanent books inspired by the last war. One does not find him there telling that he became a genuine hero, one has to find 'Undertones of War', one of the four best such accounts (ranking with Siegfriend Sassoon's Memoirs of a Fox-hunting Man, Robert Graves' Goodbye to All That and henry Williamson's 'Test to Destruction'.)

In association with Alan Porter, he discovered many MSS. of John Clare, which led to a revival of interest in that fine poet of the countryside. He has a passions for painting of the British School, especially the less trumpeted (in this he commends Colonel M.H. Grant's British Landscape Painters as an incomparable guide).

The brief review ends with: "He tells this fishing story: "I once caught a

fine Trout on a piece of bread crust in a stream not supposed to have Trout

in it."

by R.P.