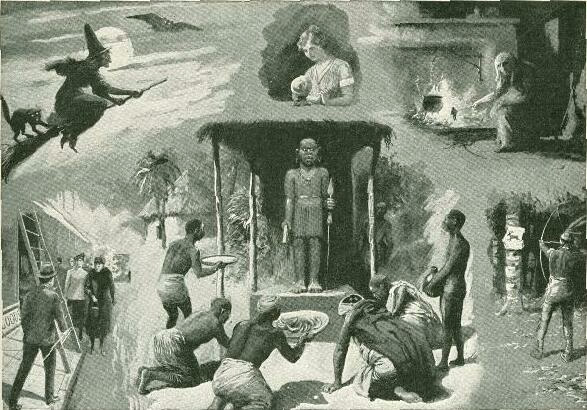

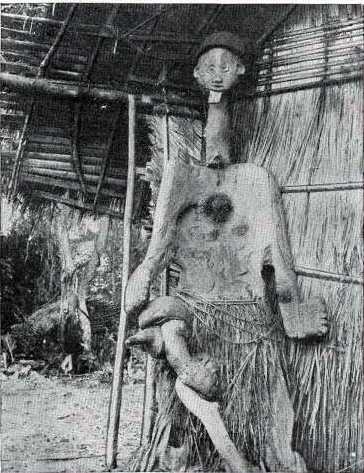

When a charm is believed to be not merely an instrument of magic but the actual dwelling-place of a certain spirit, it is called a fetish. The worship of fetishes is usually regarded as a form of religion, but it has many of the characteristics of ordinary magic. Fetishism plays a large part in the voodoo practices mentioned above.

While most forms of magic are based on the belief that evil spirits are particularly numerous and likely to injure mankind, there arises also a belief in good spirits. Along these lines, the practice of magic came to be divided into black magic and white magic; the former being used to do harm, the latter to combat this harm and do good instead.

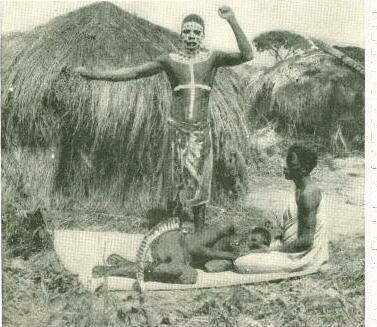

The special magician or sorcerer has existed wherever a belief in magic prevailed. Under the name of necromancers, wizards, witches, conjurors, medicinemen, soothsayers, diviners, and many other titles, they posed as persons who had unusual powers over the spirit world, and could foretell the future or read the secrets of the past. They were everywhere regarded by the people with fearful respect. In Christian countries persons suspected of dealing with the powers of evil were persecuted severely.

But many of their practices were regarded as beneficial, even in Europe, in the Middle Ages and later. Studies in magic frequently led to important scientific discoveries, for the sorcerers in contriving their magic philtres and other drugs made wide researches in chemistry, while those who studied the influence of the stare on human life learned |

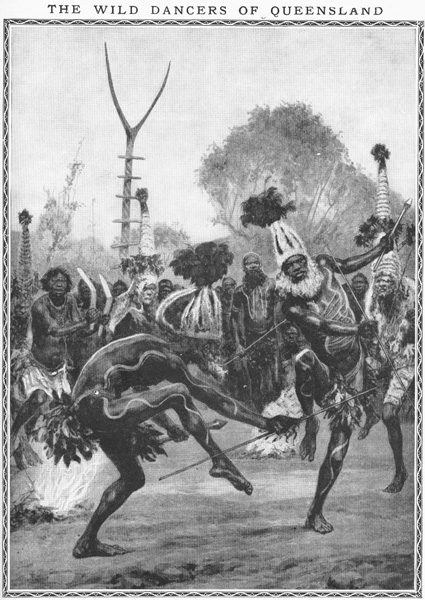

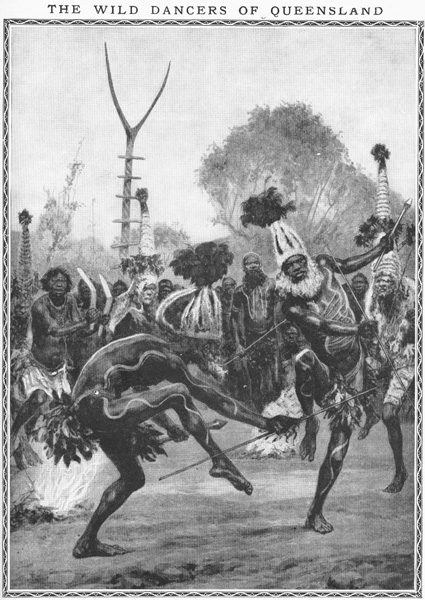

These grotesque figures are aborigines of Queensland. They are engaged in "The Dance of the Forked Stick," which is supposed to bring anything the tribe desires greatly, from rain to victory over enemies. During such ceremonies it is not unusual for the dancers to become so frenzied with excitement that they thrust their feet into the fire, apparently without feeling it. At other times they fall rigid to the ground and remain unconscious for hours.

|

many a valuable fact about astronomy.

In common practice, however, their so-called skill was directed toward interpreting dreams, getting information about the future from their "familiar''' spirits, and, in almost all cases, deceiving a superstitious public for their own personal profit. Among tho intelligent, their fraud was usually suspected, and tho Roman Cato " wondered how one diviner could meet another on the street without laughing."

While modern man prides himself on having thrown off all such superstitions, remnants of magical belief are found even among fairly intelligent people, and many of these are regarded seriously. Under this head come all the delusions about breaking mirrors, walking under ladders, the number 13, Friday, lucky coins, spilling salt, wishbones, black cats, opals, and a thousand other things that are supposed to bring good luck or bad luck. Medical superstitions also remain too numerous to mention. Any almanac will give a list of zodiac signs which are believed to govern the planting of crops, the treatment of farm animals, and to perform other functions equally magical, even to influencing the character and fate of those born under them.

In place of the old magician, we have to-day the fortune-teller, the clairvoyant, the crystal gazer, and the palmist, while many of the practices of the spiritualistic mediums, and such contrivances as the ouija board are looked upon by most scientists as relics of the magic arts.

from 'The Book of Knowledge' An Encyclopedia for All Ages. Edited by Harold F.B. Wheeler London 1930. pps. 2287 to 2291

out-of-print and copyright expired |